Transformation, logic, and invasion of neo-liberalism in advocacy spaces: Interview with MP Jessie Kabwila-Kapasula, Fearless Feminist and Women Human Rights Defender

CAL: Are you a feminist?

JKK: Oh yes I am. My name is Jessie Kabwila. I am the Publicity Secretary for the Malawi Congress Party, the main opposition in Malawi, I am also chair for the women’s caucus, I am a Member of Parliament for Salima North West, I’m a feminist, proudly feminist and I have been one since I knew who I was.

CAL: What influences your radical position on sexual reproductive health and rights in Malawi?

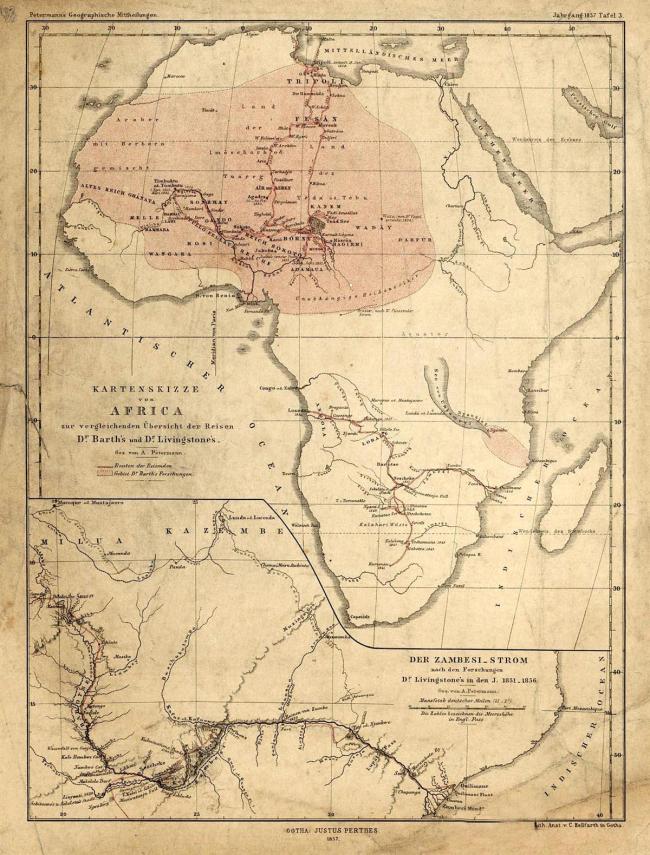

JKK: I would say it’s lived experience, what I have been through in my life and more importantly what research has shown. As an academic I usually take a position based on what research is saying. I have never understood why anybody would want to lie that being gay, transgendered or intersex is something that is not African, it’s just not true. I’ve done that kind of research myself, where I went into Malawi, to remote areas, places where people haven’t travelled. People there have never been to the US, never been to the UK, they’re just being Malawian, and I have met people who have been living; a-man and a man, sixty-four years old, and they have never been out of the country. And what struck me is they love each other. The main problem with the LGBTI discourse is that it is being discussed predominantly as a sex thing. It should rather be about people and how they love each other. It’s not as if it’s just a bunch of people who sleep with each other every day, no. So maybe the question should be, do people love differently in Africa? And I think love has no passport. Love is love. Some people love other people. Other people don’t love someone else. Just like sex, there are people who don’t have sex, are we going to arrest everybody, to say, look, you have private parts, what are you doing with them? No. As far as I’m concerned, I think it’s much ado about nothing. I think there’s this obsession to control people and what they are doing. Foucault talked about it very well in The History of Sexuality. To me Malawi is the same as someone being in chains and we lock the door and we say ‘why are you not coming out?’. Maybe it’s because you locked the door? I feel so passionate about this because I see how it is linked to HIV prevention. I think if people are hiding who cannot say that they are going to get condoms and they are going to get medication, we should understand how stigma is more of a killer than taking a knife and killing someone, because we are stopping them from being who they are. And that is impacting access to service delivery.

CAL: Why is the CSW not a transformative space for sexual reproductive health and rights 20 years after the Beijing Platform?

JKK: Because, like many institutions it has been invaded by neo-liberalism. This thing of wanting to make everybody happy. How was a statement that was not debated or consulted passed? It doesn’t make any sense and to tell the truth it’s making all this a farce. We can’t talk about transformation when there is so much silence of logic. Until and when the CSW embraces difference and we are not afraid to differ, we will not realise that it is in-between difference that actually the truth lies. We have black, white, blue and whatever colour, it is therein that we find out that we have diversity. I have never seen so many countries in the world agree in minutes. We spent much more time watching a game of football than we do ratifying a political statement-it doesn’t make any sense.

CAL: How can we push for change in language at the CSW spaces?

JKK: To be honest with you, I don’t think the issue of language is going to be won in such spaces. I believe progressive, radical people, these are not spaces for us. Those who want to ‘kick some ass’, the place is not here.

Sometimes the neo-liberal framework of discussion, leaves someone with no choice but to be very radical, in order to be heard. The real question is, can we do business-unusual, when we are behaving business-as-usual?

I don’t think this is going to bring back our girls in Nigeria, I don’t think that Boko Haram is going to be a friend of women because of this [CSW process]. If say for example, we all descended on Nigeria and demanded actions to bring the girls back, they would know that something has gone seriously wrong. I think these meetings confirm the way institutions have been invaded by capitalism and neo-liberalism, all these ‘isms’ that make us say we are fine in the morning when we are not.

*Edited for tense and shortened. E&OE.